Interacting with animals abroad can be a thorny issue. Oftentimes tourists find themselves wondering whether it’s really okay to pet this cheetah; should you actually ride that elephant; and are those captive animals actually being treated well? In this quagmire of questions, sites like the Giraffe Center in Nairobi Kenya are welcome, guilt-free destinations.

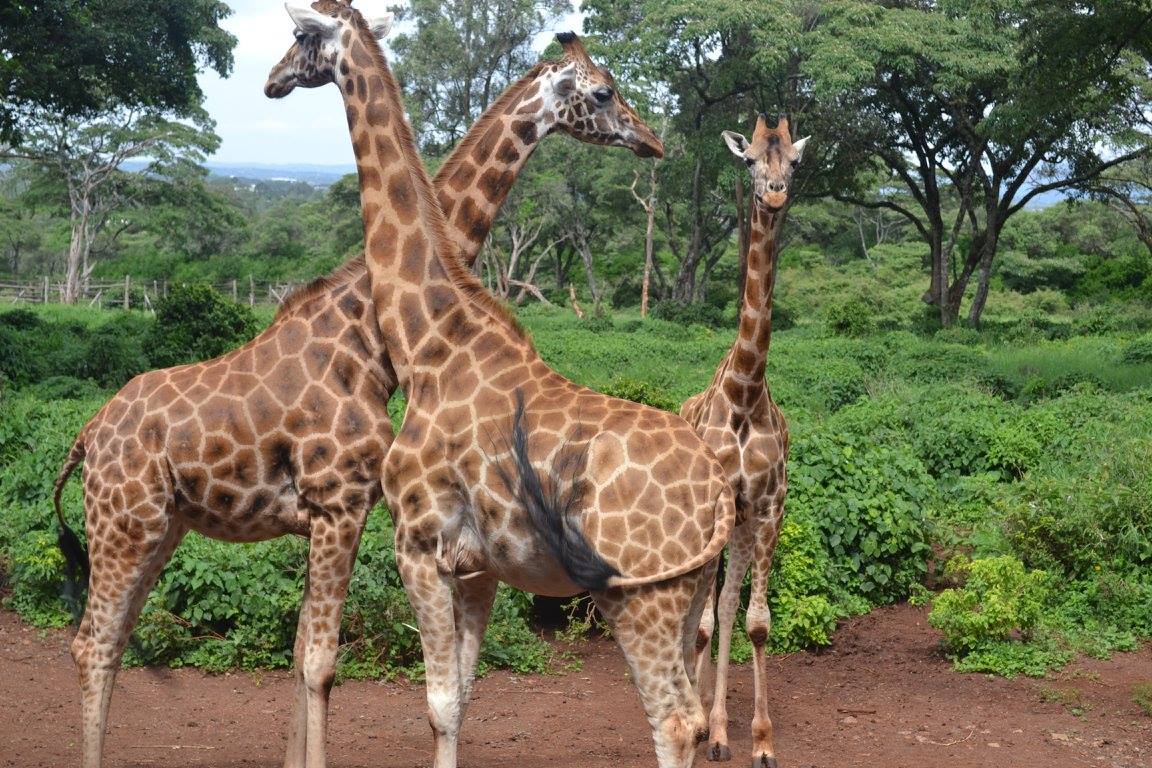

Giraffes at the Giraffe Center in Nairobi, Kenya (Photo: Giraffe Centre)

Giraffes, it turns out, are bigger than you think. I reflect on this while standing on the worn wooden slats of the feeding platform at the Giraffe Center in Nairobi, Kenya. In front of me, a striking example of the world’s tallest mammal is nudging its head – which is as long as my arm – ever closer to mine, searching for the food it clearly knows I have.

I know what I am supposed to do. I have been to petting zoos in America, I get the basic concept behind feeding an animal. The problem is, I am nervous. How much, I wonder as I stare at the giraffe in front of me, do my fingers look like food?

“Come on now,” Holly, one of my oldest friends, urges me on. We’re visiting my parents, who, instead of retiring and heading south like normal people, moved to Nairobi two years prior. I can’t imagine what my parents will say if I return from the Giraffe Center not having actually fed the giraffes.

“Here goes,” I say reluctantly, and step up to the very edge of the rail. My palm as flat as I can make it, I extend my arm out and watch, fascinated, as its head bends down and a giraffe eats – literally – right out of my hand. I am close enough to reach up and pet the coarse fur of its neck, to notice how large its brown eyes are, to see the exact contour of each of its dark tan spots.

This close, I can easily see the distinguishing marks that peg these particular giraffes as Rothschild’s giraffes. The lines between their spots are a gentle cream color, not white, and there are no markings of any kind on their legs, making them look as though they are wearing stockings. This is our first time seeing the Rothschild’s. We saw plenty of giraffes while on safari in the Maasai Mara the week before, but none like these. Once plentiful in Kenya, Uganda, and Sudan, Rothschild’s are now endangered, with only a few hundred left in the wild.

“That was awesome!” I gush to Holly, as I move away from the railing of the feeding platform. I look down at my hand, which is now very damp. “Slobbery, but awesome.”

I walk over to a station with hand sanitizer, and pour a liberal amount on my hands before coming back and taking the camera so I can snap a few thousand pictures of Holly feeding the giraffe.

A visitor feeding the giraffes at the center (Photo: Giraffe Centre)

After the feeding, we stand at the rail of the giraffes’ 120 acre enclosure, just watching. Not twenty feet away from us, a mother and baby are taking a leisurely stroll while behind them, a warthog is dozing in the shade of a tree. The baby is part of the center’s mission to increase the wild population of Rothschild’s. Roughly ten giraffes wander and breed on the 120 acre preserve at any given time. Young giraffes born at the center, however, only stay with their mothers for around two years before they are released into protected areas such as Nakuru National Park.

I like this aspect of the center. I like that I’m not sitting around worrying about how the animals are treated or how much space they have or whether they should be there. I like knowing that watching the giraffes, feeding the giraffes, is also helping to preserve the giraffes.

For the rest of the afternoon, Holly and I explore the lesser-known parts of the center. We hike around the center’s 90 acres of indigenous forest that are separate from the giraffe preserve. An avid birder, I scan the trees for species I have never seen before, while Holly drinks in the scenery, remarking on how beautiful Kenya is, how she can’t believe we are really here. Following the hike we sit down at the center’s teahouse, enjoying cold sodas as a respite from the dry heat.

The handsome grounds in which the giraffes wander safely (Photo: Giraffe Center)

As the sun begins to set and we get ready to leave, I look out at the preserve one last time, watching a mother and baby giraffe loping past through the scattered scrub and trees of the enclosure. This was the kind of place I could imagine returning to time and again, in ten years, in twenty, in thirty. I could only hope that the Rothschild’s giraffe, along with many of the other endangered animals we had seen on our trip, would still be around then, and I could once again reach my hand out over the feeding platform, and feel what it is like to feed a giraffe.