Andrew Eames follows the Danube River East to the fringes of Europe. In the process he discovers a Europe that is deeply interconnected in the present day, whilst exploring the links of the past, and how they relate to Europe’s longest river.

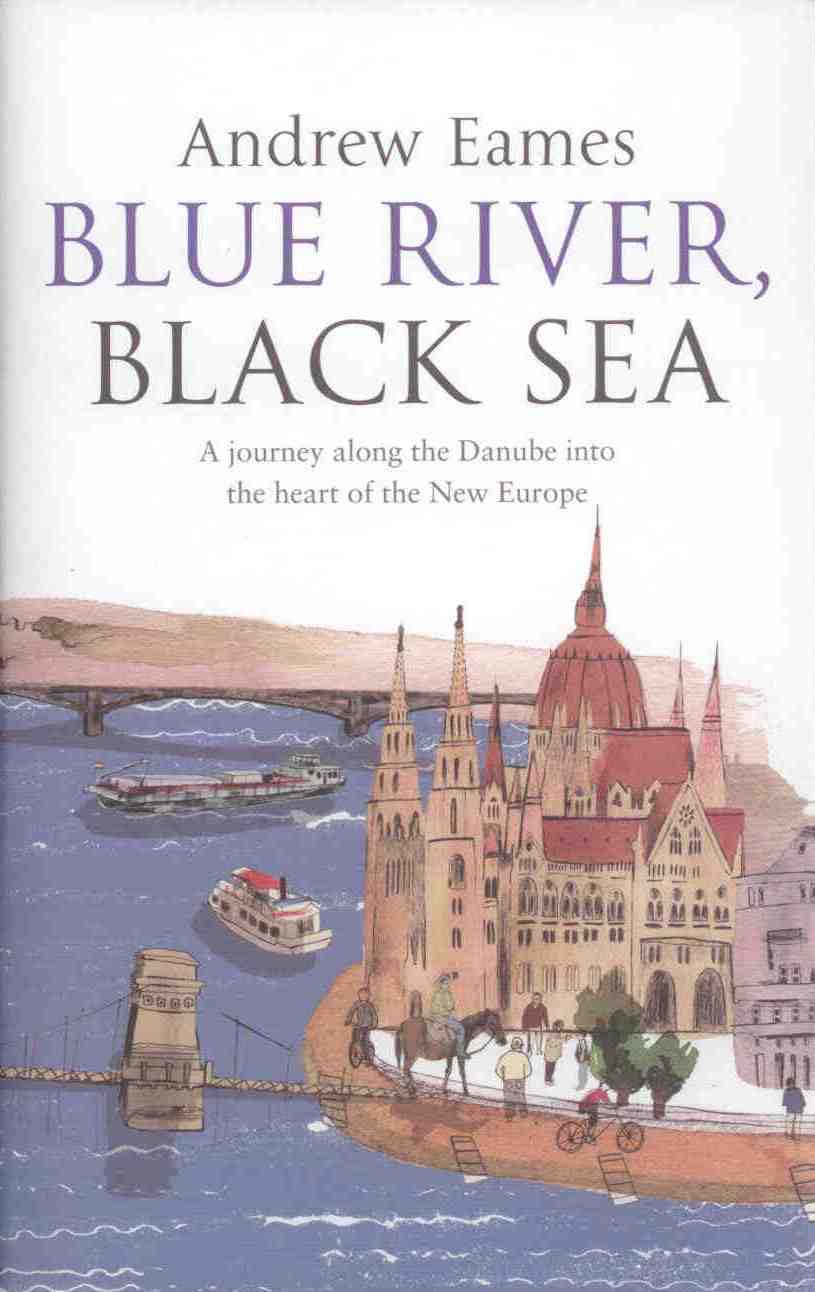

From its disputed source at Donaueschingen to the undisputed mouth in the Black Sea, the Danube river takes in a good chunk of Europe. Few major rivers pass through such developed territory along their entire length. With this in mind, Andrew Eames weaves his journey into the book Blue River, Black Sea.

The title is slightly misleading in that the Black Sea has a bit-part in the book right at the end. This is mostly a tale of a journey along the length of the Danube. Although it is only the 30th longest river in the world, it travels through more countries than all but two rivers – the Nile and the Niger. More intriguingly, the Danube connects the West and East of Europe. It starts in the Black Forest of Germany – one of Europe’s stalwart, developed nations, emerging as a marshy sprawl on the Black Sea coast of Romania – one of the EU’s newest members.

One would expect a journey down the Danube to be completed by boat, but Mr. Eames does not even set foot on a boat until he reaches Serbia, halfway along the 2840km of river. Before that he uses an inventive medley of bicycle to Budapest and on horseback from there towards Serbia. When he does make it onto a boat, it is a freight barge at the border of the EU, where we learn the drama and politics that can exist onboard. Possibly the best way to end a journey along a river however is via rowboat. Mr. Eames’s battle with the elements, “Resuming with socks on my hands and pants on my head” as he writes of his hastily assembled defences against blisters and sun, made for some of the best reading.

A Journey of Two Halves

Any trip along the length of the Danube is primed to paint a picture of the two halves of Europe, and how they stitch together. “Western civilization goes all the way to the Black Sea, or so the EU concept suggests” writes Mr. Eames. While this is not the main theme of the book per se, the divisions between neighbours are one of those interesting distinctions that a good journey will illuminate.

As his trip progresses, the sense of regulation and order diminish along the river, the policing of the waterways appearing increasingly lax as he passes into Serbia, out of the EU. This is summed up by Antar, a man working with river customs at this border crossing whom Mr. Eames meets. “In his view the European Union was just a dictatorship with more rules and regulations than communism had ever had.” The assumed truth however is that Antar is just wary of change. Similarities between neighbours, indeed between all humans, are also often highlighted by good journeys too.

Certainly one of the real strengths of the book is the way that Mr. Eames is able to unravel the tangled ball of thread that is race and nationality, particularly in Central Europe. This is a region, formerly the Habsburg Empire, and variously parts of other empires, where borders do not always fairly represent the geographical fringes of different languages and races. It is a region where Hungary and Austria are shadows of their former selves, where once they enjoyed regional dominance, and where Germans migrated away from their homeland, creating farming villages as far away as western Romania, which later became separated from their mother land by world wars and later, the Iron Curtain.

The borders of the European mainland have been redrawn so many times that settlements abound along the Danube river that seem out of place within current borders. This is nicely illustrated in a passage where Mr. Eames arrives on foot in Atel, a small Saxon village in rural Transylvania and finds his German, which he had not been able to use since leaving Austria, was once again useful because of the historic links between the two regions. Today EU membership allows the free flow of people, creating new, ever more complex migrations. Many former inhabitants of Atel moved away to live and work in Germany, but come back driving BMWs to visit friends and relatives in the summer.

Going Off-Course

However, like the buoys along the course of the Danube which demarcate sand bars beneath the surface of the dun-coloured water, the journey is weighed down somewhat. Guided by more than just the river’s flow, almost to the book’s detriment, the memory of Paddy Leigh Fermor’s On Foot to Constantinople trilogy seems to sway Mr. Eames at times from his own purpose. His own work mimics the route taken by Mr. Fermor seven decades earlier, rather than being allowed space to discover something fresh and contemporary.

True, their trips plied the same route along the river for a lot of time. This is perhaps inescapable, but the attempts of Mr. Eames to try and experience much of which Mr. Fermor experienced, such as meeting and staying with faded continental royalty along the course, seemed to force its way onto the book’s pages at the expense of the self assurance with which Blue River, Black Sea could have been executed. One incursion would have been fine, but the repeated attempts to connect with, often disinterested, members of the royal houses of Europe’s mainland, felt like interviews for an in-flight magazine without providing much any insight into more than the expense of maintaining expensive mansions.

Blue River, Black Sea unzips the centre of the continent and manages to discover, like the currents of the river it follows, that which makes Europe flow together. Despite the occasional flotsam which is carried along by the waters, the differences of European people today seem rarely to trouble more than the surface. Europe is more diverse and yet more interconnected than one could imagine, and this book is a bold testament to that.