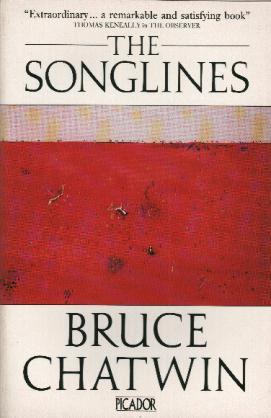

Why do we travel? It’s this question that haunts Bruce Chatwin’s classic account of a journey to the heart of Australia, The Songlines.

It a a questio n in fact that haunted the celebrated English writer most of his life.

n in fact that haunted the celebrated English writer most of his life.

Chatwin, who reinvented travel writing with his seminal book In Patigonia, was a restless soul. He travelled much of his life, which was sadly cut short in early middle age.

In the opening pages of The Songlines he offers one plausible origin for this inveterate wanderlust in a childhood spent constantly on the move.

“I remember the fantastic homelessness of my first five years. My father was in the Navy, at sea. My mother and I would shuttle back and forth, on the railways of wartime England, on visits to family and friends.”

But for Chatwin this explanation is not enough. He feels that the need to travel is much more deeply engrained in us than mere childhood experience.

For Chatwin the origin of our wanderlust goes right back to the dawn of human life on Earth. For Chatwin to be a human is to be a traveler…

Into the outback

For his book the writer went to Alice Springs to find out more about about Australian Aboriginal culture. The reason he chose Aboriginals was because he felt they were the best-preserved nomadic culture still in existence.

Chatwin’s premise, that he underlines quite early on in the story, is that at heart humans are nomads. It’s only in relatively recent history – the last 15,000 years or so – that we settled the land. Before that and, for most of our history since we evolved from apes, we followed the migratory herds, living constantly on the move.

The Songlines are a metaphor for this nomadic spirit. They are a labyrinth of invisible paths that criss-cross the Australian outback. According to Aboriginal Creation myth ancient beings walked over these paths literally singing the land into existence.

As well as being a beautiful concept, for thousands of years the Songlines also served a very practical purpose. Since the songs contained an index of the geographical features of the land along a particular path, an Aborigine who knew the song could use it to navigate the land.

On his journey to learn more about The Songlines Chatwin butts heads with the darker reality of the contemporary condition of Aborigines.

Before he’s even made it to Alice Springs he sees a fight between two miserably drunk Aborigines at a roadside bar. They are being egged on by a clientele of truckers and construction workers who call them names and hand them smashed bottles to attack each other with.

Local color

In Alice Springs he meets Arkady Volchok, a campaigner for Aboriginal rights and an expert on the Songlines.

Volchok introduces him to various Aborigines in the area and while the encounters are sometimes amusing, they’re never very illuminating. I think part of the reason for this is that Chatwin had already made up his mind about Aboriginal culture and its place in his theory of life. Because of this he often feels less concerned with learning first-hand from the local than with impressing on them his own vast stores of knowledge.

In one fairly typical encounter he meets an old Aborigine, Father Flynn. At first the man has no interest in talking to him. Then Chatwin starts telling him about gipsies.

“’I cannot see,’ said Flynn, ‘what gipsies have to do with our people?’

‘Because gipsies,’ I said, ‘also see themselves as hunters. The world is their hunting-ground. Settlers are ‘sitting game’. The gipsy word for ‘settler’ is the same as the word for ‘meat’.’

Flynn turned to face me.

‘You know what our people call the white man?’

‘Meat,’ I suggested.

‘And you know what they call a Welfare cheque?’

‘Also meat.’

‘Bring a chair,’ he said. ‘I want to talk to you.’”

The gem of knowledge about gipsies was also typical of the kind of thing Chatwin loved to collect in his notebooks. In his wanderings over years he had amassed an inventory of small facts, anecdotes and quotations like this that supported his thoughts about our inherent nomadism, and at the centre of the book there’s wonderful section where he places all his notes together.

He quotes from the likes of Rimbaud and Baudelaire as well as including relevant snippets from his own travels. His notes are fascinating and persuasive but, like the whole of The Songlines, also a form self-justification. Chatwin was addicted to travel and he needed a way to understand that addiction.

The notes start with a quote from Pascal: “Our nature lies in movement; complete calm is death.”

Chatwin died in 1989 from Aids. Ever the storyteller, he got round the taboo surrounding the disease at the time by claiming to friends he was suffering from a rare fungal infection picked up on a trip to China. He was just 49.