Travel guides usually describe Idaho Springs as “former” mining town. And while it’s true its copious days are over, spend any time up here and you feel it: This small Colorado mountain town about half way between Denver and Dillon along I-70 has never ceased being all about mining. Veins of ore still permeate the surrounding mountains. Miners blood still runs through the people’s veins.

Idaho Springs (Photo: Snap Man via Flickr)

Gold Diggers

It was a cold day in January of 1859 when George Andrew Jackson, on a hunting trip from his native Missouri, discovered the first gold in Colorado at the confluence of what today is Chicago Creek and Clear Creek. His campfire had thawed the ground where he sat, so the lonesome explorer panned some sand in his drinking cup, washing out gold nuggets. Jackson marked the spot where he’d found gold and returned that spring with 22 men and tools. By summer, Colorado’s first mining district was formally recorded.

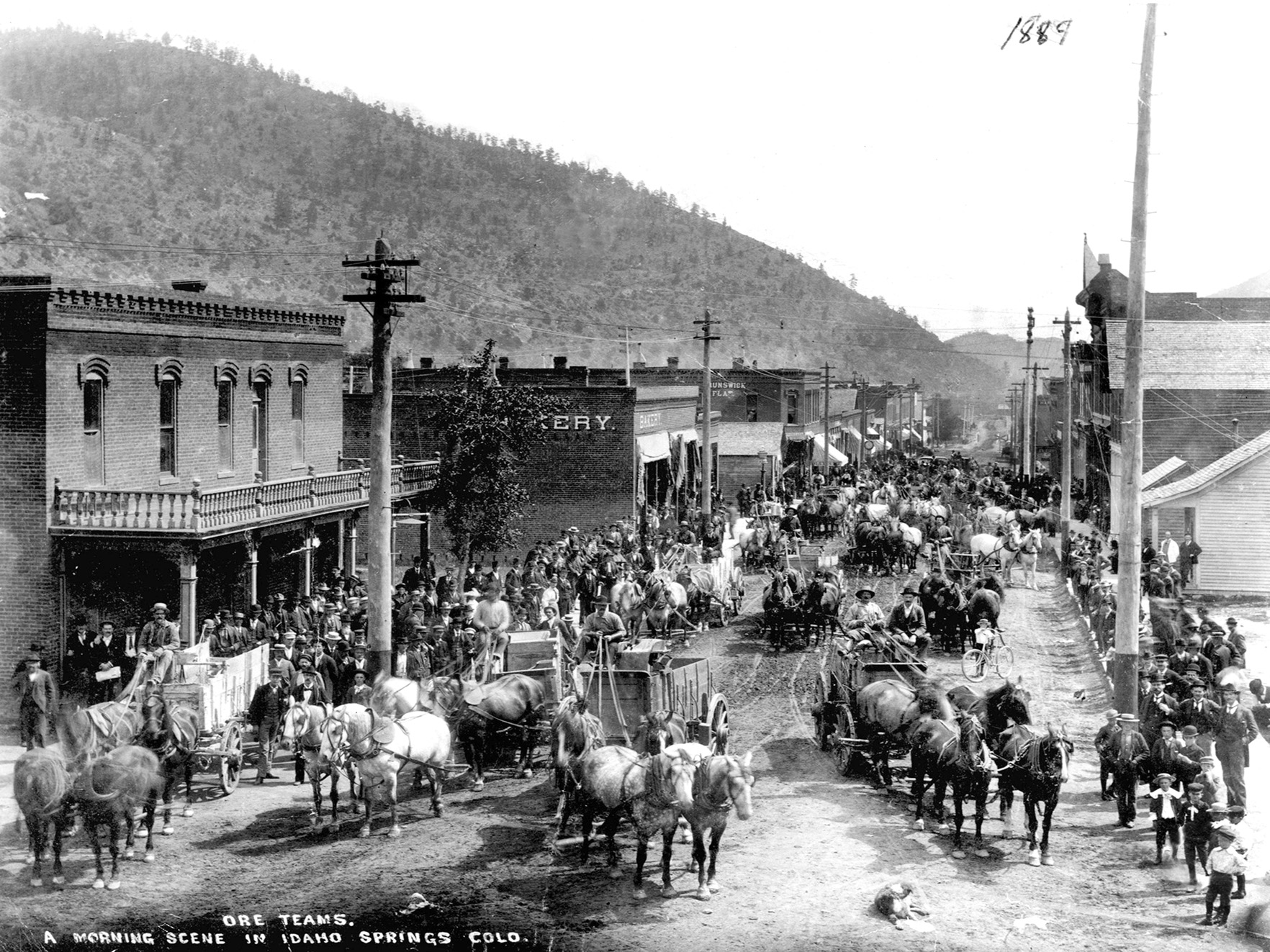

Word spread and the great Rocky Mountain gold rush promptly ensued as 50,000 prospectors poured into Clear Creek Canyon, digging for gold from sunrise until sunset. Their women and children followed, and soon fine homes and stately business buildings substantiated the golden era of mining in the area.

Idaho Springs’ population exploded during the Great Rocky Mountain Gold Rush. Miner Street was buzzing with prospectors hoping to strike gold here in 1889. ( Photo: Historic Society of Idaho Springs)

The Argo Tunnel and Mill

Soon the easy placer gold was panned from the streams. The miners followed the trail of gold to its source in the mountains and hard rock lode mining began. Crews raised ore from 1000 feet and deeper, 1000 pounds a load. But the deeper the miners dug, the more water they encountered. The pumps could no longer efficiently keep the shafts from flooding.

With Central City on the other side of the mines sitting 2000 feet above Idaho Springs, a tunnel was needed to drain the water downward. Mining magnate Samuel Newhouse began conceptualizing what would become the world’s largest mining project, facilitated by the world’s longest tunnel: the Argo.

Construction began in 1893 and was completed in 1910. 4.16 miles (6.69 km) long, the Argo Tunnel intersected nearly all of the area’s major gold mines, provided water drainage and the underground logistics needed to transport the loaded ore cars to the new five-story state-of-the-art Argo Mill at the tunnel’s portal in Idaho Springs. The gold mill opened in 1913 as the world’s largest, most modern mill. Operating around the clock, the “Mighty Argo” processed 300 tons a day and only required 3–5 men per shift to run.

The mill tragically flooded in 1943. Cave-ins killed four miners and ended mining operations.

Today, visitors can tour the Argo Gold Mine and Mill, pan real gold and exit through the gift shop. “The Argo stands testament to the hard-rock miners of the days gone by,” says its manager Bob Maxwell. “The Argo represents the days of industrialization.”

Argo Gold Mine and Mill Museum. (Photo: J. Conn via Flickr)

The Heritage Visitor Center in town houses a free museum with unique exhibits of the town’s mining history, early life and the significant role it played in establishing not only Idaho Springs but the state of Colorado itself. “It was a progressive little town, but rugged,” says Carla Allan, who has worked at the visitor center since she retired in 1996.

Idaho Springs’ other landmarks and attractions include the Charlie Tayler Waterwheel at the foot of Bridal Veil Falls, the Jackson Monument, erected in honor of George A. Jackson and Engine No. 60 and Coach No. 70, remnants of the Colorado & Southern Railroad operations in Idaho Springs.

Hot Mineral Springs

If the gold rush hadn’t put Idaho Springs on the map, the Indian Hot Springs undoubtedly would have made this quintessential Old West whistle-stop famous in time. Long before white settlers arrived, the Ute and Arapaho Indian tribes soaked in the hot springs along Soda Creek.

Naturally, the hardworking miners unbent their bone-tired bodies in the springs, as the early mining camps lacked hot water for bathing. It’s said that Augusta Tabor, the first wife of prospector and politician Horace Austin Warner Tabor — a.k.a. The Bonanza King of Leadville — was the first white woman to use the hot springs. Famous visitors who followed her on the resort’s guest list included the Vanderbilts and the Roosevelts; John Denver and Clint Eastwood in modern times. To this day, spa-goers come up to the Indian Hot Springs for therapeutic treatments, massages and geo-thermal cave baths.

Up and Down Miner Street

Standing testament to the West that was, Idaho Spring’s gas-lit downtown district, a four-block stretch lined with quaint buildings from the early mining days, has been declared a National Historic District.

Grab a doughnut or apple fritter at Morning Gold Bakery for breakfast before shopping the unique small shops along Miner Street that offer souvenirs, local art and crafts and Tibetan jewelry.

At Beaujo’s, hungry travelers get a real feel for the Colorado lifestyle. The popular pizza joint, famous for its “mountain high pizza pies” (ordered by the pound), is decorated with antique pick axes, a floor-to-ceiling replica mineshaft and photos and paintings depicting local life during the golden era.

Outdoor Adventures

Only a 40-minute drive away, Idaho Springs makes for an ideal day trip to escape Denver. “You go 10 miles in any direction and you are in very pristine landscape,” Maxwell promotes the destination’s outdoor recreation potential. Hiking, biking, horse back riding and trout fishing await.

More adventurous visitors can zipline across the roaring rapids of Clear Creek or tear downstream on a whitewater raft. The Clear Creek Rafting Company offers daily trips throughout the summer.

Rafting on the narrow Clear Creek. (Photo via Clear Creek Rafting)

Mountain Living Without Paying the Prices of the Famous Mountain Resorts

Fewer than 2000 residents live in Idaho Springs, many of them commuting to Denver or westward to work at the ski resorts. “It’s the middle of the road for people who want mountain living but can’t afford Vail,” Maxwell says, dishing the millionaires live in posh Summit County just up the Interstate. Describing the town’s down-to-earth vibe, the manager of the Argo assures visitors dressing up is not required here: “Blue jeans are just fine in any restaurant.” And Allan couldn’t agree more. “It’s not a whoop-de-do town,” she relents. “People come to Idaho Springs because they like Idaho Springs.”

“So many people who live here still have a connection to mining,” Maxwell sums up. “It’s intertwined in our souls.”