Aracataca, the birthplace of late Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, still retains the character that inspired his greatest work.

A Gabriel Garcia Marquez commemorative mural, Aracataca (Photo: Stephen Woodman)

From the moment my bus rumbles to a stop outside Aracataca station, I have the sense that an entire sleeping village is rising from my memory. The scorched streets, rusted tin roofs and dusty almond trees—I instantly recognise it all from my imagination.

For fans of late Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the town where he was born does not disappoint. On my taxi ride to the hotel—in a cycle rickshaw—I see that Aracataca’s every detail echoes the mythical town of Macondo described in the Nobel laureate’s fiction.

We pass down a series of unpaved streets, where cooking smells and car exhausts hang heavy in the air. Lively discussions flare up around coffee carts and countless yellow butterflies dance in the glaring sun, as if in tribute to those that swarm through Macondo.

While the novelist, who was affectionately known as Gabo, left Aracataca when he was eight, he frequently told reporters that nothing interesting ever happened after that age.

“One Hundred Years of Solitude,” the multigenerational tale of the eccentric Buendia clan, is a thinly disguised reworking of his own colourful family story. The magical realism genre he popularised, with its blend of autobiography and myth, was directly inspired by his childhood experience of this sleepy Colombian town.

An unpaved street, Aracataca (Photo: Stephen Woodman)

A Local Gabo Expert

“Nothing, or very little, has changed in Aracataca for thirty years,” says Frank Dominguez, a Gabo expert who has read “One Hundred Years” from cover to cover a total of 12 times, including a couple of times in reverse chapter order. Sat with Dominguez and his wife Renata in the implausible heat of their living room, I listen as he describes the novelist’s return visit in 2007.

“There were so many people who came from all different parts. He couldn’t move because of the crowds.”

Dominguez works as a school teacher by day, but reads feverishly at night. He has written several critical investigations of Gabo’s work, his latest exploring the influence of the Bible on his novels.

“He’ll go crazy from all this reading,” Renata says as he ambles off to collect it.

Tour guide Rodolfo Rodriguez, Aracataca (Photo: Stephen Woodman)

The Tour

Rodolfo, my enthusiastic tour guide, is taking me around town to visit local characters with an insight into Gabo’s early life. Luis Bichara is a retired shopkeeper who greets me with a gentle squeeze of his hand.

“I was born in 1927, the same year as Garcia Marquez,” he says with pride.

98-year-old Maria Magdalena has difficulty hearing and is partially blind, but she smiles and nods in recognition when my tour guide mentions Gabo. She still remembers the restless boy she cared for as a nanny.

Rodolfo takes me to various sites that I recognise from the novels. At the town’s entrance is a river, like that in Macondo, running “along a bed of polished stones,” which are “white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs.” The telegraph office, where his father used to work, is now a sparse museum. We stop to pay respects at Melquiades’ grave, a tombstone erected in honour of the irrepressible wanderer who brings all kinds of inventions to Macondo.

Scattered around town are numerous monuments and murals depicting Gabo and his work.

On the southern edge of town is the “Remedios the Beauty Park,” a tribute to the bewitching Macondo local who ascends into heaven.

Rodolfo tells me the ascension story was based on the claims of a local woman whose granddaughter had run off with a lover. To avoid scandal, she put the word around that she had been assumed like the Virgin Mary.

Near the monument is the railroad that brought modernity to town. The United Fruit Company, a powerful U.S. multinational, built the track during the banana boom of the early twentieth century. With the railroad came electric lighting, a cinema and other modern conveniences, as well as immigrants from every corner of the globe. Almost overnight, the town was transformed into a cosmopolitan hub as waves of Venezuelans, Jamaicans, Syrians and others arrived along with the new found prosperity.

Yet when the Great Depression struck in 1929, the United Fruit Company left for good, leaving a melancholy nostalgia and startling unemployment.

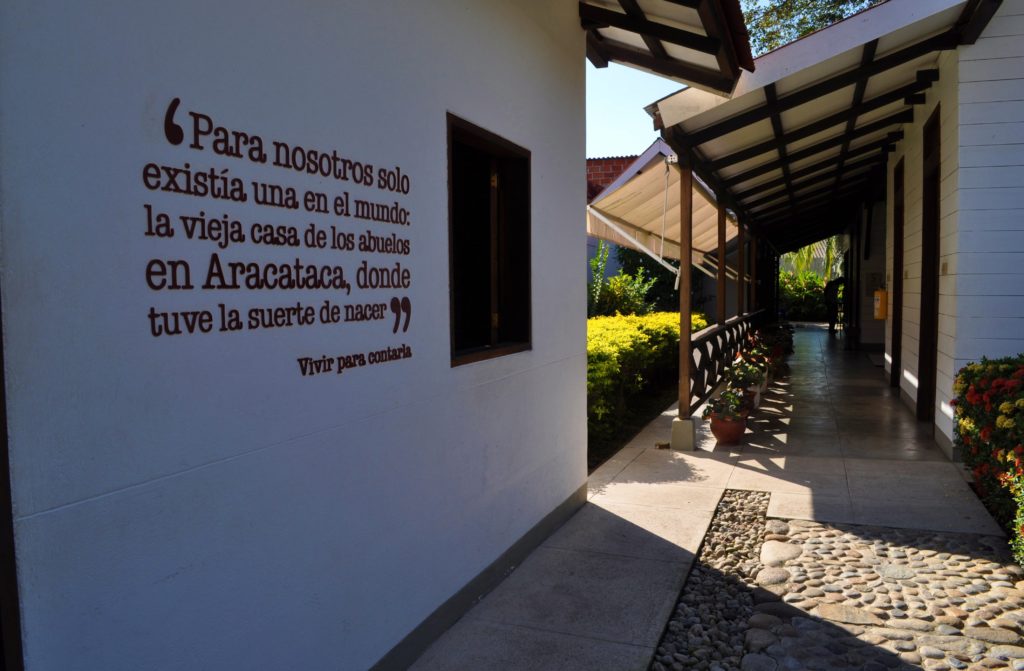

The exterior of the Gabriel Garcia Marquez House Museum, Aracataca (Photo: Armando Calderon via Flickr)

The Family Home

In the centre of Aracataca is the highlight of the tour—a reconstruction of the family home on the site where Gabo was born. We walk down a corridor leading to eight successive rooms: his grandfather’s office, various bedrooms, a dining room and a kitchen.

Gabo’s family moved to Aracataca so his grandfather, Colonel Nicolas Marquez, could escape the remorse of having killed a man in a duel. The new house failed to restore his peace of mind, and his grandfather would regularly remind Gabo that there was no greater burden than that of having ended another life.

The Colonel was instrumental to Gabo’s development as a writer. He gave him a tattered 2,000 page dictionary, which the grandson pored over as if it were a novel. The indigenous servants were also central to his formation, and would speak endlessly about good and evil spirits.

The Dutch Melquiades

The Aracataca tours now given by Rodolfo were started by a Dutch citizen, Tim Aan’t Goor, who arrived in 2007 and adopted the surname Buendia in honour of the fictional family.

With his bright shirts, leather sandals and fondness for walking sticks, Tim’s appearance recalled that of the mythical wanderer Melquiades. At first, his presence prompted suspicion among locals.

“It’s a very tight-knit community,” Tim says, speaking on the phone from the United States. “Some people thought maybe I was involved in drugs, or a spy.”

Yet Tim’s plan to attract visitors soon kicked into effect, and his local status grew when tourism rapidly expanded. Nevertheless, when he left for California in 2014, the year of Gabo’s death, visits once again dropped off. Now, only a few locals like Rodolfo still promote the effort.

Tim draws a link between the region’s poverty and its untapped potential for tourism.

“Most locals don’t understand the magnitude of Gabo’s work and the magnitude of Aracataca itself,” he says. “There are literally thousands of people who can barely scrape by… people kind of accept it because that’s the only thing they know.”

While Aracataca and Macondo have become synonymous across the globe, in the face of the daily pressures of poverty, most locals are unaware, or are unable to take advantage of the town’s cultural significance. This was reflected in 2006, when a referendum on officially changing the town name to Aracataca-Macondo was abandoned because almost no one turned up to vote.

Tim would like to see local businesses actively attract tourism to lift the local economy. He still has high hopes for Aracataca. After all, for Gabo readers the town will always be the quintessential Latin America.

“I really believe that it is a town that more people should see and understand,” Tim says. “Aracataca is like a blueprint for Colombian history. Through the history of Aracataca the gates to Latin America open up.”

Local teenagers sitting on Melquiades’ grave, Aracataca (Photo: Stephen Woodman)