Every year, hundreds of thousands of baseball fans make the pilgrimage to Cooperstown, New York, to visit the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Surrounded by forested hills, the quaint, former frontier town lies near the southern tip of the pristine Otsego Lake. A visit to Cooperstown feels like stepping into a time capsule, where the spirit of early, small-town America remains preserved.

Designed to give 10- to 12-year-old players a professional baseball experience, Cooperstown All Star Village hosts weeklong tournaments (Photo: Cooperstown All Star Village)

Days into a long-awaited tournament at Cooperstown All Star Village, my nephew’s team is two runs behind. It is the last inning of the semi-finals. So far they’ve won every game, but if they lose now, they are out of the tournament. If they win, they move on to the finals. As his team runs into the dugout from the field for their final up-bat, the coach warns against trying to go big. No homers, he says. Keep the ball on the ground. Round the bases. Let’s see some real baseball.

The bleachers are packed. All eyes grow wider, straining to see the batter through the chain link fence that restricts our view. After the first batter is out, fear and excitement pulse through my veins, as if I am the one about to thump my bat against home plate. My nephew is up. He swings. Crack! The ball is going, going, gone. At once, the crowd is on its feet, whooping and clapping. High fives all around. We are one run closer to a tie.

Then, just as quickly, we return to our tense postures. The next batter heads toward home plate. Our hands clap. Our feet stomp. Some holler –“Here we go kid!” “Keep your eye on the ball!” — attempting to create momentum, as if we all carry the weight of the team’s comeback on our shoulders. For a moment, I am a young girl again, wringing my hands as my older brother takes the mound to pitch another inning. Back then, I would feel his every move — every grimace after a hit, every grin after a swing-and-a-miss, every ache as he rolled his arm and massaged his left shoulder — as if it were my own. This, I remember now, is baseball.

The Birthplace of Baseball

Serving as a research center for the history of baseball and home to the sport’s most prized relics, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is much more than walls lined with inductee plaques (Photo: David Casteel via Flickr)

Between games, my family and I head into the historic district of Cooperstown to visit the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. On the steps outside the brick building, teams pose for photographs, young hopefuls yearning to one day join the 312 legends already elected into the Hall of Fame. Though most are players, the awardees also include executives, managers, even umpires. And, yes, one woman: Effa Manley, the civil rights activist and co-owner of the Newark Eagles, who won the Negro League World Series in 1946 (one of many victories in her effort to promote African American players to play in the Major Leagues).

I ask the man at the ticket counter for the inside scoop, something about the town and the Hall that most people don’t know. Contrary to popular belief, he says, baseball was not invented in Cooperstown: the Mecca of baseball has been built upon a lie.

The Hall of Fame opened in 1939 to celebrate the supposed 100-year anniversary of the invention of baseball in Cooperstown. Even so, a small sign, crammed in between other relics that line the walls, debunks the legend that Abner Doubleday, a Civil War hero, introduced the ballgame to his playmates on a farm field in 1839. Accompanying the sign is a tattered, coffee-ground brown, hand-sewn baseball, purportedly used in that first game. The story was based upon a letter from a man who swore he was at the field that day. Though slim, this was enough evidence to launch a campaign to prove that baseball was born in the United States, during a time when the country was carving its own national identity.

The “Doubleday Baseball” was found in a farm attic in 1936 and purportedly belonged to Abner Graves, the man who claimed to be present when Doubleday invented the game (Photo: Neil R via Flickr)

More plaques and glass cases filled with century-old uniforms and trophies tell the story of how the professional version we watch today evolved from ancient stickball games to those based on family and neighborhood rules to the first club team, the Knickerbockers of New York City. The modern game echoes the 20 rules the Knickerbockers established in 1845. Soon the sport was swept into the industrial tide of the era. The baseball clubs’ shift into money-making machines is captured in a posted New York Time headline from 1891: “…no longer a sport, but a business.”

After opening in 1939, the Hall has become a living history of a game that is still very much alive. Though I am no baseball history buff, I find myself struggling to move quickly. Everywhere I turn, something catches my eye. I could spend all afternoon in Babe Ruth’s corner alone. Eyeing the black and white photos and newspaper headlines feels like being transported back in time to the roaring 1920s. Displays showcase pieces of his lifetime, including a brick from his father’s saloon, a stone from the boy’s school he attended in Baltimore and the wooden bat he used to hit his 60th home run in 1927. The Sultan of Swat would go on to hit a total of 714 home runs in his 22-year career, opening the door for future record breakers by smashing the Impossible.

The five center plaques honor the Hall of Fame’s first class of inductees in 1936: Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner and Babe Ruth (Photo: Ron Cogswell via Flickr)

Stretching the Boundaries of the Game

While my parents distract my daughter — who’s smitten with the bright orange and yellow San Diego Chicken costume of the Padre’s silly, unofficial mascot — I pay homage to the players that also shook the frames of the sport sans the raving fans.

The Diamond Dreams exhibit of women in baseball features both the movie A League of Their Own and the real players from the All American Girls Professional Baseball League, launched to save professional baseball during World War II. Seeing the women’s uniforms again — the foxy, short skirts — I shudder, remembering a scene in the film after a player slides and earns a deep purple bruise the size of a cantaloupe around a bloodied shred of skin on her thigh.

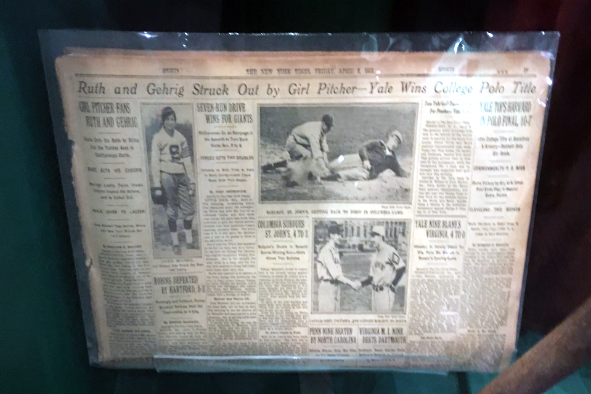

In reality, the league lasted over a decade. More than 600 women played during the 1940s and 50s. Women attempted to make their mark in the major leagues as well. My smile widens when I read the aged newspaper piece about Jackie Mitchell, who played for the AA team the Lookouts in 1931 as one of the first women signed to the Major Leagues. The 17-year-old pitched a scrimmage game against the New York Yankees and struck out both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Mitchell became a legend in her own right, even though her contract, like many other female players’ contracts, was later voided.

“The New York Times” article “Girl Pitcher Fans Ruth and Gehrig” (Photo: Bre Power Eaton)

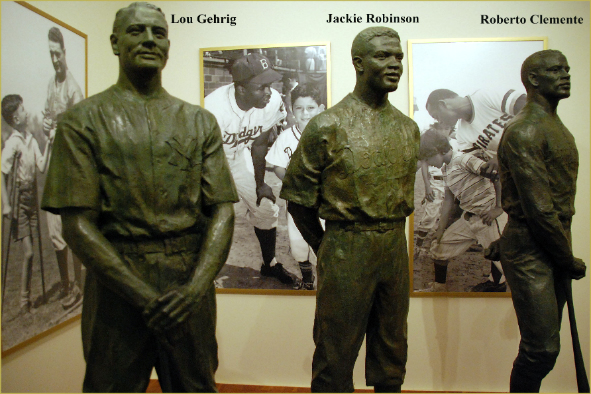

Nearby is the exhibit Pride and Passion: The African-American Baseball Experience. Slowly, I round the room, following two parallel timelines that juxtapose the Civil Rights Movement in America and the history of black players in baseball, dating back before the Civil War. I’ve always thought that Jackie Robinson was the first African American to play in the Major Leagues, so I am surprised to learn that Moses Fleetwood Walker, who was born on the Underground Railroad, played in the Major Leagues in the American Association in 1884. The pernicious racism that remained after the Civil War and led to the Jim Crow Laws also precluded Walker from playing another season and other African American players in the Negro Baseball League from integrating into the all-white Major Leagues until Robinson’s courageous debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Witnessing the spurts of progress along both timelines, sparked by revolutionary players in both the history of our country and baseball, I am awash in a mix of emotions: fear for the lives of those who played despite death threats, anger at the bigoted gatekeepers, sadness over the slow march of progress, but mostly awe and hope inspired by the tenacity of the black men who played on despite the barriers they faced and still face as our timeline continues both on and off the field.

Bronze statues of Roberto Clemente, Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson honor the Hall of Famers, who overcame poverty and racial/cultural bias, for their exemplary “Character and Courage” both on and off the field. (Photo: Ron Cogswell via Flickr)

Before leaving the Hall of Fame, I am struck by how integral the game’s evolution has been to our progress as a nation. Baseball has functioned as our cultural Petri dish, where boundaries have been tested and bent, reflecting the growing pains of the American experiment, likewise still evolving and very much alive.

The Final Inning

All we need is one run to tie, to keep the game alive another inning. Jazzed in the stands, the crowd aches for that kind of moment, when, in the face of two strikes, Babe Ruth pointed two fingers toward the stands, then smacked the next pitch over the center fielder, up into the seats, hitting his mark.

But there would be no historic moment. After the third out, my nephew’s team does their best to collect themselves (a few quickly wiping tears from their eyes) before lining up for the requisite high fiving and exchange of “Good game!” with their opponents, who are unabashedly triumphant.

Before leaving the parking lot, I gaze out over the baseball fields, surrounded by the forested hillsides that lured William Cooper to purchase the land in 1786. The burgeoning frontier community was also founded on a revolutionary idea. Rather than following the status quo of indentured servitude, Cooper sold parcels of land and gave his buyers 7 to 10 years to pay off their debt. He further supported new settlers with supplies to survive the winter.

Though Cooperstown may not be the birthplace of baseball, the quaint frontier town continues to preserve this legacy of community, of bringing together hundreds of thousands of players and fans from far and wide each year, united by passion for the game.

A view of Cooperstown dressed in fall colors, hugging the tip of Otsego Lake (Photo: mpburrows via Flickr)

A view of Cooperstown dressed in fall colors, hugging the tip of Otsego Lake (Photo: mpburrows via Flickr)