The Greyhound bus service in the United States has decent claim to being one of the worst travel networks anywhere on Earth. Journeys are interminably long, comforts are rudimentary, and a sense of real danger constantly pervades; it’s not even cheap. But there are few experiences that bring you closer to the American soul.

Go Greyhound! (Photo: Thomas Hawk via Flickr)

Just before the shooting started Carolyn had said all people on Greyhounds look like they are either going to, or coming from prison. I already knew there was some truth to this.

I watch her later, when we are finally allowed off the bus: her purple, tie-dye tee-shirt, the grimy hold-all slung over her shoulder, and her greasy ginger hair, scrunched back and sweating in the Alabama sun. She says hello to her sister, then turns to wave me goodbye with her non-bandaged hand.

I think of her smell when we were crouched next to each other between the seats, listening to gunshots crackle. She smelled of cornstarch and candy bars – in short, of America – and I had wondered if it might be the last scent my nose would ever know.

For an emancipating moment, now, I wonder if I could go with her; leave the Greyhound for Birmingham’s cracked concrete, and say, simply: How about I stay with you? I’ll pay my way, of course, then you can show me where you come from, and the horses you said still walk down the main street of your town. I’ve known her for less than four hours, but hadn’t we survived something together? And the South is famous for its hospitality.

More to the point, after what has just happened, do I really want to stay on this thing all the way to D.C.? And in all the madness that followed the shooting, I haven’t really had a chance to discover her thoughts.

I do stay on the bus. I think over the other things Carolyn said to me, and I watch her go.

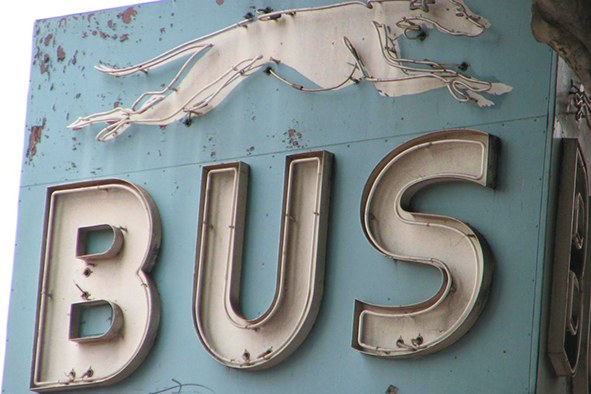

Fading Greyhound sign (Photo: Karyn Christner via Flickr)

The Alabama Freeway

When you are released from federal prison in the U.S., the state provides you with a grey tracksuit, a see-through plastic container for your belongings, and a free ticket on the Greyhound back to wherever it is in America that you call home. And because this system has proved so efficient, in recent years the government has started to use Greyhounds to transfer prisoners, unaccompanied, between penitentiaries as well.

We pull north from Birmingham, away from danger, back onto the interstate and toward our next destination. All destinations are prisons of a sort, I think, but in transit everyone is free. From the long bus window, though, the city’s sprawl is slow to give up to the country; the Waffle Houses still compete with discount firework stores and weatherboard churches for drive-thru custom.

Greyhounds are enclosed and they are slow. They work on their own schedule, not yours. The buses go most everywhere in America, but nowhere directly. They zig-zag across the face of the United States like prospectors lost in search of a seam.

The bus I am on cannot be less than twenty years old. It has a hand painted image of a greyhound dog on its flank and upholstery worn smooth by decades of human freight. When we are on the road, the bus driver protects himself from his passengers behind a sheet of bulletproof glass – I know now that this is no unnecessary precaution.

Nashville Greyhound Station

From the bus station the Nashville sunset is a smudge in orange pollution and the city skyline looks like a child’s building blocks, unevenly stacked then forgotten. Cold lighting makes the city feel close, and keeps the oncoming darkness at bay.

My guidebook says there are over 30,000 registered musicians in Nashville. That’s 30,000 registered dreams. There is no sign of them here. All I’m doing is waiting on a transfer and this Greyhound station could be any number of others. Of course, I am afraid.

It is a low building, open plan inside, and with large windows. There are several lines of blue plastic chairs, but most people have slung their bags down any which place, and are squatting, haphazard across the dirty floor. Regular announcements burst from the tannoy, but they are static charred and incomprehensible, only feeding disorder. Unease is marked in every face: that tightening of muscles around the top of the cheeks, an involuntary straightening of the mouth, and eyes drawn wide, reluctant to blink. The smell is of grease and sweat, candy and corn.

There are some people at the station who do not look like they are waiting for a bus: tall, black men, dressed in over-sized baseball shirts and caps, with trousers that ride low. They stalk shark-like through the crowds and I cannot decide if they are patrolling a patch, or if their purpose is affected; that they are just passengers like everyone else.

There are security guards, too, old and overweight to a man. Their guts stretch fabric and hang low over belts, holsters, and guns. They stand near water coolers, and the ‘No Firearms’ signs that menace the station walls. I am certain they are well acquainted with violence.

As I make my way out to the bus, I am joined by a short man in his early twenties. He is of Vietnamese descent, and perhaps as round as a person could expect to be.

“Hey,” he says, out of nowhere, “These things kind of scare me, so, uh, mind if I ride with you?”

He tells me his name is Rob, and is from a town near Baltimore.

“We get about 73 murders a year,” he says. “It’s only a small town, so that’s a lot.”

Rob has been in Nashville helping a friend move. He doesn’t like country music, or anything much else, it seems. He doesn’t have a job, but when I pester him he says he wouldn’t mind being an actor.

“Like Johnny Depp,” he says, or maybe a stand-up comedian: “I dun’ know, people tell me I’m funny.”

Greyhound on the road (Photo: Richard Bauer via Flickr)

Johnston City, Tennessee

The otherworldliness of overnight travel: the bus pushing through indifferent darkness, along freeways that only run straight, and, as you drift in and out of consciousness, it feels that this is how it might be to travel between the stars; slowing to stop in towns with names that mean nothing, which appear from the night like space ports then fade into oblivion once they are left behind.

At around three in the morning, the Greyhound pulls into one of these nowheres, and, because I am more awake than not – still too on edge to fully sleep – I leave it for a cigarette. Rob is asleep now, and snoring softly. I climb over him, down onto the platform.

The air is still full of Southern heat, and insects dance in the illuminations as they would anywhere else. I step away from the bus. On the platform are two men with little luggage and vacant expressions. They were not waiting for our bus, but another. I think of an American Vladimir and Estragon, forever waiting for their Greyhound to show, and because of this, at the same time, forever on the road, forever free.

“Need a light?” a tall, tracksuited man asks me. His hair is cropped, and he is carrying with him a military hold-all. His lighter’s flame is turned high, and he holds it up like the trigger to a fuse. He says he is in the army, that he’s just got back from Afghanistan. He tells me things had been pretty hairy ‘in country’ but that travelling on Greyhounds still worries him. He says he is from Florida and that he is headed to Maryland to see his girl.

“It’s been nine months,” he tells me. In the way he says it there is bravado — “the kinda shit I’m gunna do to her” — and there is fear — “a lot can happen in nine months.”

I finish my cigarette and head back to the bus. As I do so, he calls after me.

“Hey man, we’re in Johnston City.”

“Yeah?” I say.

“Like in the song!”

“What song?” I ask.

The Virginia Freeway

A sickly dawn breaks over Virginia. I have travelled more than a thousand miles, but from the freeway America looks the same. The road is still straight, and its ragged edges are still ragged. There is forest either side, but in the early light it too seems homogenous and industrial.

Behind me, two faceless veterans have started to talk about Iraq. I listen, but their conversation is conducted in a code made of numbers and foreign words.

“You were in the 112th?”

“111th –”

“Ah, I had a buddy in the 112th.”

“– in Tarmiyah.”

“I was in the 32nd Artillery”

“The 32nd? With M270’s?”

“M270’s and Paladins. But we did a lota dismount stuff in Chikook.”

“Jus’ the good ‘ol M16?”

“– and the Mossberg 590.”

“Shit, the 590!”

“Get much contact in Tarmiyah?”

I think about the idea of war being fought by accountants, I think about Orwell’s Newspeak, I think about weapons as commodities, and their operators as consumers. I wonder: What can these “numbers” do to a human body? It’s unfair. I know almost nothing about war, or how people ought to talk about it.

I let my attention slip from the veterans. Rob is still snoring. I look at his face, at his double chin, and the pimple that has formed on it during the night. I wonder who he loves, I wonder who loves him. He told me last night that his father fought for the Americans during the Vietnam war, then emigrated when the war was done. In a town near Baltimore, which now boasts 73 murders a year, Rob’s father worked in a 7/11 and he built a new life.

The forest has ended now. I look up out of the window at the pageantry of the free world; at the strip malls and the slogans as they slide on by.

Hopefully not a final resting place (Photo: Patrice Levesque via Flickr)

Carolyn

Carolyn had begun to talk to me almost as soon as I got on the bus in Jacksonville. If I’d had to guess her age, I would have said at least fifty. She swore that she was only thirty-seven. Our conversation did not last long, but once she began speaking, she was breathless, and did not stop. She told me how she had cut off her finger before getting on the bus way out West but hadn’t had it looked at because she was fearful of hospitals – “Last one I went to was tuh get mah appendix out. Turned out I were eight months on with mah second”; she told me how she was returning home to a bad man, who she said she ought to have shot; she told me her favourite kind of movies were snake movies – “Like, ones with snakes in ‘em”; and she told me about the horses that she said still walked down the main street of her town. I imagined I was not the first person to have heard her stories on the long haul across the country from Phoenix, and I felt neither would I be the last.

I do not know how much of what Carolyn told me was true, and how much was fabrication. I do know that she spoke to me entirely without prejudice. It did not matter I was a white English male, what she talked to me about — truth or lies — would have been the same regardless.

We knew something was wrong the moment that we pulled into Birmingham station from the crowds spilling onto the sidewalk. I had never heard the sound of gunfire before, so did not recognise the high octane cracks sounding from nearby for what they were. Carolyn did. So did most everyone else in the bus, and we were crouched down below the windows before the driver had shouted back that this was what we ought to do.

“Folks, I am getting us outta here,” he called to us hero-like, then executed a rushed but effective maneuver to get the bus back out of the station: the reality of real life heroics shown up as the ability to perform a three point turn under pressure. For maybe thirty seconds, which felt like longer, I could hear the uneven rhythm of gunshots from outside. My imagination seethed with images of what the bullets might be connecting with, and I waited for them to violently rupture our Greyhound cocoon.

That did not happen. Instead, the driver took us a couple of blocks safe distance, where we idled for about thirty minutes in the hot sunlight, the panda cars of Birmingham Police Department blazing past us to go deal with whatever was happening over at the station.

Carolyn had forgotten about me by this stage. After the initial shock, the event at the station had everyone talking almost all at once, and she was talking to all of them. There was the speculation, the telling of similar stories, the inevitable commiseration of what a dangerous place America had become. Somewhere debate opened up between an enormous black lady and a camouflage wearing white man. I believe it was about gun control, though found it hard to follow, and it was cut short by the bus driver calling out again over all of our heads.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced in the manner of a man who had spent his whole life talking to crowds. “I have just heard over my radio that the incident is over.”

A few shouts sounded from the bus as people demanded to know what had taken place.

“It seems that a somewhat disturbed gentleman was unhappy that he could not get a refund for the 12:54 that he had missed to New Orleans. He had a firearm on his person and as his consternation increased he began unloading it into the ceiling. As you saw, the police department was called, and the shooter was apprehended. I have been led to believe that no fatalities nor injuries have resulted from this situation.”

A genuine collective sigh sounded from the bus. And as we pulled back out into the road, back toward the station, all the talking at once began again. Carolyn turned to me once more, as though there had been no break in our conversation, though I had to believe that it had been the shooting incident and not my company which prompted her to say: “Ah swear thisus been the worst damn bus ride of mah life. When ah go back to Arizona, ah’m gun’ take the plane.”

Waffle House (Photo: L.W. Yang via Flickr)

D.C.

I arrive in Washington D.C. after more than 24 hours of travel, emerging from the bus with newborn exhaustion. Rob is going further, so he stays on board. He hardly says goodbye. My friend Will is at the bus station to pick me up. I climb into his Ford and Greyhound America is already behind me. It is Sunday, so Will takes me direct to church.

A heady sunlight pushes on America’s capital, and its buildings glimmer with unreality. Because of me, we are late to the service, and the main hall of the church is already full. Will and I head to one of so many basement chapels, like nuclear bunkers, where widescreen televisions relay the preacher, a charismatic pedant, lecturing on text and salvation. I can hardly stay awake.

The next day happens to be the fourth of July, and Will takes me to a barbecue with his friends. Most belong to his church and most work for the government. A few delight in telling me they cannot tell me what they do.

At one point during the barbecue, I find myself sat in a circle in which the guests – clean skinned, intelligent, Republican – take turns, in honour of the day, halfway mocking, halfway serious, saying what it is they love most about America.

“The freedom,” utter five separate voices, although exactly what each person means by this, they find hard to explain.