Kamakura’s shrines and temples stir a sense of calm and wonder. Exploring their magnificent prayer halls and manicured grounds with locals can make the experience all the more memorable.

Kenchoji entrance (Photo: RyosukeYagi via Flickr)

Our train pulled into Kita-Kamakura. The station seemed quaint and quiet compared to the commotion we’d left behind at the city center. My friend Mimi and I scanned our Suica cards to exit then looked for our guides: two elderly Japanese gentlemen whom I had been teaching English for a few weeks. I had immediately grown attached. When Kotima Nao-san and Yasunori-san offered to show me around Kamakura, the ancient capital city known for its wealth of shrines and temples, I’d jumped at the chance.

“Ohayoo-gozaimasu,” we said, greeting our guides good morning with one of the few phrases we knew.

Underneath his black leather jacket, Nao-san wore his characteristic sports coat and the large black-framed glasses that took up half his ageless face. Yasunori-san wore a puffy purple jacket and chuckled when I used his nickname “Ace” that his badminton teammates had called him in high school. Both of their smiles widened when I introduced Mimi, whose blonde hair was a rare sight, especially outside of the more touristy areas of Tokyo and Kyoto. English signs and information were equally rare in Kamakura. Our day together would be a special treat: an opportunity for my students to practice English conversation and a chance for me to learn more about the temples and shrines I had visited many times, admiring their beauty without knowing exactly what I was looking at or why it mattered.

Zenzai and green tea (Photo: Breawna Power Eaton)

Engakuji

After entering the temple grounds, we paused in front of a two-story wooden gate, topped with a winged roof, whose tips curved toward the grey winter sky. Though the sanmon gate was built in 1783, the grounds themselves were founded in the late 13th century in honor of those who’d perished while fighting off two Mongolian invasions. Nao-san explained that Engakuji ranked second of the five great Zen temples of Kamakura.

When I’d first arrived in Japan, a friend had pointed out the country’s knack for tiered classifications – the number ____ of the ____ of the _____. Rank matters and competition is fierce, I’d learned, yet humility is honorable, as is not standing out. These contradictions fascinated me as much as our guides’ revelation that one of Buddha’s teeth was enshrined on the temple grounds.

We walked into another wooden building, where a gilded Buddha sat cross-legged atop a large red lotus on the altar. Our eyes followed the bare wooden columns up to meet those of a black and white dragon on the ceiling. The weathered painting – the snarling nostrils, fangs, and snakelike body engulfed in flames and plumes of smoke – held us captive until our necks ached.

Back outside, we strolled slowly, admiring the grounds that were gorgeous even mid-winter. The leafless maples and flowering trees added an austere contrast to the greenery that had not given into hibernation. Even outside the prayer halls, I felt the need to whisper so as to not disrupt the calm that rested over the entire compound.

After passing a tranquil pond near the back of the grounds, we paused at an outdoor tea garden and huddled close on benches surrounded by naked trees. The ume (plum) would blossom before the sakura (cherry) our guides said. For now, tiny pink blots the size of tear drops on the bare branches remained the only promise of blooms to come.

Soon a tray of earthenware bowls filled with frothy pea green matcha arrived, accompanied by sugar-cube-like treats shaped like bees.

“First, you eat a sweet,” our guides said.

Mimi and I placed a sugary treat on our tongues and watched as our guides picked up their tea bowls with their right hands and then placed them on their left palms.

“Turn the bowl away from they front,” they said and rotated theirs clockwise twice.

I looked at my bowl, then at Mimi to see if she’d figured out which side was the front. Our guides watched. Still clueless, I moved my bowl twice and, like a child eager to please her teacher, was relieved when they did not correct me. Tradition not only seeps into the ceremonial: there are very specific, correct ways to do almost everything here. I watched carefully and waited to lift my bowl until after my guides had, just to make sure there was not a traditional way to take the first sip.

The earthy flavor was strong and bitter, but softened by the sugar still dissolving on my tongue. We tipped our bowls again and again until we’d sipped the last drops then turned the bowls counter-clockwise, back to their original positions.

“Wait,” one said, when I started to put mine back on the tray. Though we’d finished our tea, the experience was not complete until we’d wiped the rims of our bowls with napkins, as we would if we were passing around one cup to share during a formal ceremony.

“How do you find the front?” I asked, still unsure if I’d actually found mine. The bowls were plain, without a singular painting of a crane or sakura or anything in particular that caught my eye.

They tried to explain, and I nodded, even though their ability to find the front still seemed like a magic trick I could not master, much like paying my bills on time at the convenience store or counting out the right amount of change.

Steaming bowls of matcha (Photo: Breawna Power Eaton)

Before leaving we took a detour up a steep cement staircase to another tea cafe perched atop the wooded hillside. The small patio overlooked verdant hills and deep valleys that come fall would seem set afire, awash in red, yellow, and orange foliage. Our guides brought us trays topped with blue and white striped cups of green tea along with palm-size lacquered bowls. We lifted the lids to reveal a reddish black soup with floating white blobs.

“Zenzai,” one said. “Red bean soup with mochi. It’s sweet. Do you want to try?”

They encouraged us with head nods and glints of excitement in their eyes. Hesitant not to burn our tongues, we sipped. The broth was sweet like they’d said, as if the soup was made of Boston Baked Beans candies from back home. I’d tried other desserts made from sweet bean paste before, but had bitten into them thinking the thick, dark paste would be chocolate fudge. That let down, again and again, had made me hesitant to try the soup. Maybe knowing what to expect this time had made all the difference, or I was finally acquiring a taste for Japanese sweets, but I was not lying when I looked up from my bowl and smiled, said it tasted good, and sipped again.

“You like it?” they asked with a tone of curiosity and glee, as if to hear the compliment again.

Their grins grew after we’d successfully fished out the gluttonous rice dumplings with our chopsticks. The mochi was flavorless, but the soft and chewy texture was as comforting as the warmth that filled my body and eased the chill in my bones.

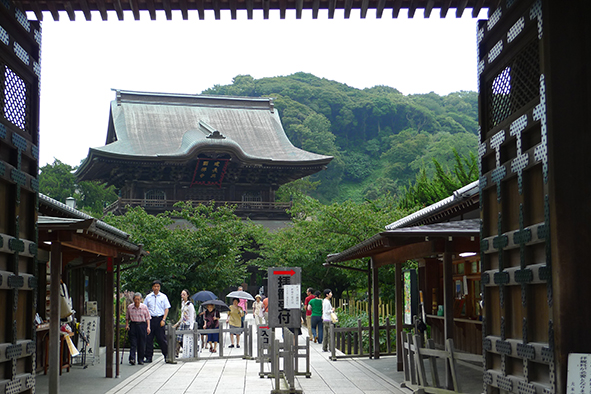

Prayer hall at Kenchoji (Photo: Breawna Power Eaton)

Kenchoji

As cars zoomed past, we walked on the sidewalk, up a hill. Kenchoji, they explained, was actually the first Zen temple built in Kamakura in 1253. Once inside the grounds, we paused in front of an oxidized bronze bell that hung under a thatch roof. Alongside it was a large wooden gong that looked more like a log that could also be used to pound down a door during battle. On New Years Eve, they explained, the bell is rung 108 times to rid worshippers of their worldly passions and troubles. Throughout the evening and into the night, locals wait in line to ring the bell to begin the year anew.

Nao-san guided us up a narrow cement path flanked by groomed pines, like overgrown bonsai, and led us to his family gravesite in the private graveyard Mimi and I could never have entered otherwise. As Nao-san stood before the stone monument, the final resting place of his family members’ ashes, his pride washed over us all.

“Arigatou,” I said, thanking Nao-san. “It’s beautiful.”

He beamed.

This would not be the first or last time that I would feel honored by the intimacy of a moment, by my Japanese friends’ and students’ generosity; when I would wish that I had come prepared, that I had something – flowers or incense – to give in return.

Before leaving, we visited what would become one of my favorite buildings, home to a Buddha statue far more weathered than the dragon painting we’d seen at Engakuji. Remnants of red and gold paint smudged the statue, walls, and ceiling. Earlier we’d seen a miniature Buddha statue that worshippers run their hands along, touching where they have pain and then rubbing the corresponding areas on their own bodies. The walls that surrounded this ancient Buddha seemed to have been worn in the same way, not by visitors’ hands, but decades of prayers whispered before the altar. Though I did not bow in prayer, I stood in awe before the statue, wondering how many others have done the same.

Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine (Photo: itchys via Flickr)

The Number One Shrine

Our last stop was where many travelers head first – Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, Kamakura’s most important shrine. I had already visited the site many times; had walked up the path, famous for the cherry trees that beckon locals and travelers to walk with craned necks under their canopy of pink and white in early spring; had learned about the symbolism of passing through the red torii gates, where we left the secular world behind and entered sacred territory; had learned how to cleanse my hands at the fountain. But I had forgotten the steps. So I listened attentively as our guides showed us how to use the bamboo ladle to pour water over the left hand and then the right, then cup a hand to fill and rinse the mouth. Before setting the ladles down, we tipped them to allow the remaining water to wash over the handle.

Past the performance hall, painted in brilliant red, green, and white, we walked up yet another steep staircase to the main hall, from where we looked back over the city, teeming with cars and people. As we approached the altar, I asked Ace if he would teach me how to pray. We each tossed a coin into the offering box. He rang a bell that hung on a thick rope in front of us, waking the deity. I followed his lead as he bowed then clapped twice, before closing his eyes to pray.

The first time I’d climbed these steps I wondered if I should pray as I do not believe in the deity of the Minamoto family, who’d founded the shrine almost a thousand years ago, or the samurai culture that it honored. Participating had felt wrong at first because of both this disbelief and my own beliefs, which had shifted over the years. Standing next to Ace with my head bowed I was drawn in by the act of tradition, the symbolism of taking a moment to stop and honor something greater than myself. Before turning around, we bowed once more.

A Lasting Souvenir

We walked toward the city center on Komachi-dori, a famous shopping street packed with teens in school uniforms, tourists, and rickshaw drivers. Our guides had spoiled us throughout the day, paying for everything, but Nao-san still wanted to buy us a souvenir.

“Would you like to try traditional Japanese pickles?” he asked, leading us into a store.

Once inside, we followed Nao-san from sample to sample, trying to guess each crunchy, pickled mystery. Garlic, eggplant, daikon radish. Nao-san revealed each answer giddily. Whether we guessed correctly or not, he was delighted all the same.

At the train station, before heading our separate ways, we swore we’d meet again to visit the temples and shrines we were unable to explore that day. But we never did. Even so, each time I had visitors, I took them to Kita Kamakura and stopped to sip tea in the garden. I could not remember which hand should hold the bowl or which way to turn it, how many times. I failed to summon the wisdom of my guides. Still, with eager eyes, I would watch as my guests cupped their hands around bowls of pea green tea and closed their eyes, savoring the earthy scent. Whether they exclaimed, “So good!” after they sipped or grimaced, I smiled as my guides had smiled, delighted all the same.