Fresh from the New York School of Art, a twenty-four-year old Edward Hopper set sail for Paris. Remaining there between 1906–1910, the French capital left an indelible imprint on the imagination of the painter who would become America’s quintessential 20th-century artist. Here, we follow the artist’s footsteps and track his inspirations in the City of Light.

Hunched over his easel on the stairway of his new Paris lodgings, the young American artist dabs his palette. The scent of oil paint rolls through the air. He looks to the window, then to the steps as they catch the light. Pitching his brush-strokes slow and lithe and brown, he traces the composition from the door down the winding stairs and around the corner and out of sight. Stairway at 48 Rue de Lille is one of the first of around 50 paintings Edward Hopper produced during his brief but fertile period in the French capital.

To gain a deeper perspective on Hopper’s time in Paris, I met Didier Ottinger, Centre Pompidou’s deputy director. A passionate Hopper aficionado and keen documentarian of the artist’s Paris years, Ottinger explained that Paris was a major turning point for Hopper. “It was here that he discovered impressionism which was very seminal. After his first dark-coloured American paintings – in Paris, he moved to something much fresher; more colourful, more sensual, more spontaneous,” he said.

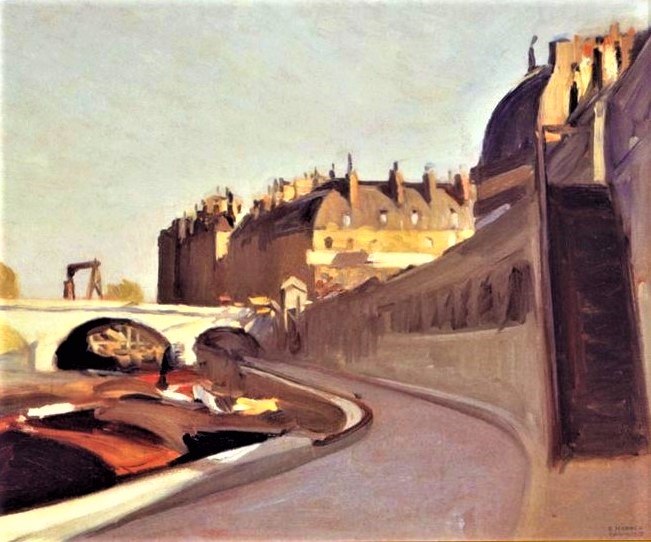

Hopper clearly couldn’t resist the magnetic pull of water that his upbringing on the Hudson River had imbued in him. Of his Paris paintings, nearly a third focus on the river Seine. So I started my quest to locate the scenes in Hopper’s paintings by strolling up the Seine’s left bank.

I arrived at the first location, eponymously titled: Quai des Grands Augustins. Just as in Hopper’s painting, the Seine’s sweeping towpath reels into the distance, the honey-stoned buildings hovering above it basking in a pale light. Edging north Le Pont Royal – a popular landmark with Hopper due to its proximity to his living quarters at the Baptist Mission in Saint Germain des Prés – illustrates the artist becoming more at ease with himself; his pictures starting to blaze with luminous burnt oranges and lustrous pale yellows.

Moving further up river to the last location of Hopper’s left bank compositions, I reached Pont Alexander III, and savoured the boundless views of the Seine and its bobbing barges. Hopper’s terse vignette Steps in Paris focuses on the flight of steps ascending to the famous bridge, where two distant figures dwell beneath a powder-blue sky. The most prominent figure seems to be looking in the direction of the Grand Palais, the gallery where Hopper had once absorbed the works of impressionists Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro and Cézanne – artists who would inspire him to infuse his paintings with more colour.

Gleaming among the splendour of the Champs Elysées, the Grand Palais’ magnificent art-nouveau-domed roof cuts an elegant figure into the Paris sky. Constructed for the 1900 Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair), today it serves as a rotating exhibition space for some of the world’s greatest works of art.

Leaving Alexandre Pont III, I took a leisurely walk to the Baptist Mission on Rue de Lille. As it was in Hopper’s day, Rue de Lille and its surrounding area are punctuated with art galleries, design boutiques and antique shops, with a clutch of vintage-styled bistros that hark back to Belle Époque Paris – some more convincingly than others. The Mission gave the maturing artist a solid foundation in the city from which to experiment with the new moods, forms and perspectives that would help frame his emerging trademark style.

The Mission’s caretaker kindly gave me a private tour of the locations in the building where Hopper had painted. He led me up four flights of stairs to the exact spot where the fledgling artist had brought Stairway at 48 rue de Lille to life. Again, little had changed. The chocolate brown doors and curving mahogany staircase were still intact, though the steps were a lighter shade.

Café culture

Unlike his later American paintings, Hopper’s elementary studies of Parisian street life don’t articulate scenes of ambiguity; his characters aren’t stranded in momentary limbo or in solitary delay. Produced with watercolour and ink, they do, however, reveal the young artist’s humour and his developing eye as a social observer. They also mirror his comment in a letter to his mother that the city encouraged “a pleasure-loving crowd that doesn’t care what it does or where it goes, as long as it has a good time.”

In Men Seated at Café Table, Hopper casts a wry smile at the city’s inhabitants; two sharp-faced gents in flowing trench-coats and caps idle over a carafe of wine while keenly surveying their surroundings. Similarly, in Couple Drinking he fixates on a man and woman who look like paid-up members of the bohemian bourgeoisie. They are arty and sophisticated, and sit nonchalantly with their hands clutching glasses of vin rouge. Due to the characters appearing on blank backgrounds it is impossible to determine the locations where they had been sketched. “Probably in the bohemian cafés and streets in and around the Saint Germain des Prés district near where he lived,” said Ottinger.

Café culture in Paris has been a stalwart part of Parisian life since the Belle Époque. A befitting café for Hopper fans (or fans of art in general) is La Palette on Rue de Seine. The café acted as something of a social nucleus for painters such as Cézanne, Picasso and Braque, as well as American literary luminaries Ernest Hemingway and Jim Morrison, who probably penned their ponderings here while quaffing a few carafes à vin. Today, its dowdy yet decadent art-deco back room is populated by Beaux-Arts students, local traders and curious tourists who enjoy an apéritif and a croque monsieur.

Another notable Saint Germain des Prés spot for an apéro is Bar du Marché (also on Rue de Seine). To the tune of 1960s west-coast jazz, waiters in dungarees and flat caps weave the terrace serving drinks and snacks with trays aloft. Quirky conversation with random visitors erupts out of nowhere. Though if you are an observer rather than a talker, Bar du Marché is also a wonderful spot to take in the breeze and bustle of St Germain des Prés – a corner of Paris like nowhere else in the world.

Hidden inspiration

Scenes like those in Hopper’s later American paintings can be seen in Paris today. On Rue de Bac, near the Baptist Mission, I spot two theatre actors caught between shows, tête-à-tête beneath a neon-red bistro sign, their minds buried in their scripts. A few cafés down, a woman with long raven-black hair sits behind an art-deco window and gazes out at the world over the pages of a magazine.

I traced Hopper’s steps from 48 rue de Lille back out onto the Seine, Hopper’s favoured painting spot. In a letter home to his mother he explained: “I could go a few steps and I’d see the Louvre across the river. From the corner of rues de Bac and Lille, you could see the Sacre Coeur. It hung like a great vision in the air above the city.”

I turned right at the top of Rue de Bac and walked one block. Stopping outside Café Voltaire and casting an eye down river toward Pont Royal, I realised I had inadvertently stepped inside the scene from Hopper’s Le Bistro, a painting that during my research had proved difficult to locate. I held the picture to the sky, comparing the scenes. A startling resemblance unfolded. The café table hugging the pavement, the gentle hump of road, the swaying trees, and the rhythmical arches of the Pont Royal rooted beneath a pale blue sky all triggered the intuitive sense that I was standing in the exact spot from where the scene had been captured.

But the whereabouts of Paris Street – Hopper’s placid yet atmospheric portrait of a simple Paris street scene – proved elusive. Most Parisians I asked pointed to streets veering off Rue de Seine, a charismatic stretch in the city’s intellectual heart of Saint Germain des Prés. Peppered with tantalising bistros, patisseries and chocolatiers, I zigzagged in and out of the street, hedging guesses and grasping at maybes – to no avail.

Leaving an impression

Alongside the wealth of European impressionist painters Hopper witnessed in the galleries, two French impressionists who cast a galvanising spell over his oeuvre were Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet. Both painters had produced masterpieces musing on the loneliness of crestfallen women in cafés: Manet’s La Prune, and Degas’ L’Absinthe. In Hopper’s later American painting Automat (1927), a woman sits alone in a roadside cafe. The cafe is brightly lit – and empty. She gazes blankly into a coffee cup. The bleak precariousness of her place in life heightened by the stream of street lights behind her disappearing into the darkness of night.

Hopper’s inspirational cues in the capital were not limited to visual art, but can also be pinpointed in French verse. This is piercingly evident in his bizarre homage to Paris – and ultimately to the poem ‘Sensation’ by Arthur Rimbaud – via the painting Soir Bleu. Rimbaud was a powerful point of reference for Hopper, and it was from the verse: “In the blue summer evenings, I shall go along the paths” that Hopper had drawn inspiration for the painting’s title and theme. “Soir Bleu was essentially a direct transposition of Rimbaud’s poem,” said Ottinger.

Depictions of nocturnal solitary scenes from window perspectives were a dominant motif in Hopper’s later work, as they were in the prose of another of his favourite French poets: Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire maintained that we see less looking out from windows than we do looking into them. Viewed from the exterior, his poem ‘Windows’ transfixes on the night-time Parisian rooftops and a still-life window scene:

“There is nothing more profound, more mysterious, more pregnant, more insidious, more dazzling than a window lighted by a single candle.

In that dark or luminous square, life lives, life dreams, life suffers.”

From Night Windows through to Hopper’s magnum-opus Nighthawks – in which four mysterious characters are suspended in the pallid glare of a spartan diner and shadowy New York street – each scene could well be a summoning of Baudelaire’s poem.

This, alongside the French poet’s preoccupation with penetrating the darker undercurrents of his city’s subconscious – its transience, its modernity, its alienation – plausibly served as a forerunner to Hopper’s ensuing forays into urban isolation and disconnection.

When probed about his Paris years, Hopper remained largely mute, commenting only that “it took me ten years to get over Paris.” It was a revelatory remark. The visual, sensual and emotional assault that Hopper had experienced during his Paris sojourn unleashed a spellbinding narrative that became a pivotal reference in some of his most iconic works. Like the echoing charms of a long-lost lover, Paris’s dreamy, intoxicating soul had seized the young artist’s senses and lingered quietly in his heart – right up to his last brushstroke.